Lee Kai Chung performs artistic research on the entanglement of geopolitics, coloniality and its affective fallout.

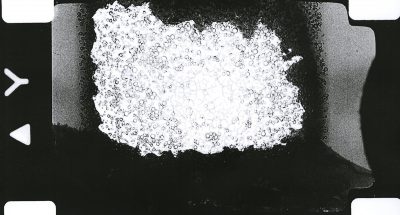

In his early years, Lee was inspired by the lack of proper governance over public records, then he develops his archival research methodology as his key artistic practice. Through research, social participation and engagement, Lee’s work resonates with historical narratives, which demonstrates that individual gesture as a transition between politics and art.

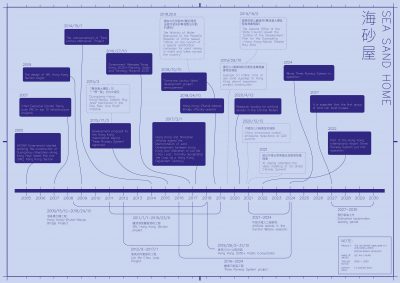

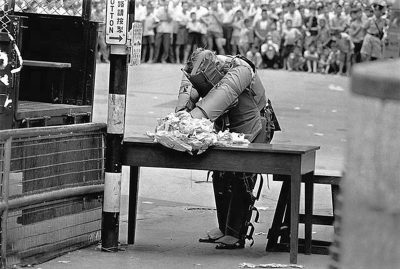

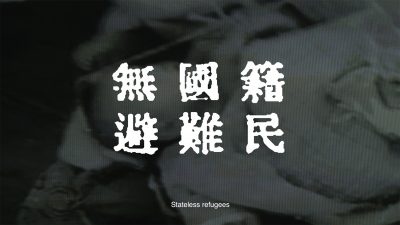

In 2017, Lee initiated a hexalogy of consecutive practice-led research projects under the theme of Displacement– based on the understanding of human migration and material flow in the shadow of the colonial matrix of power, the projects scrutinise the agency of Displacement, expand the perception of the notion to affective, anachronic, transgenerational and geopolitical aspects of human conditions entangled in Eurasian problematics.

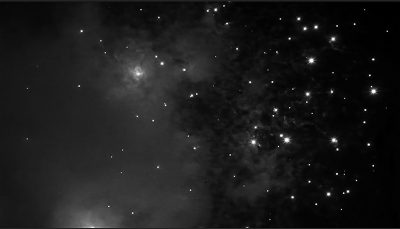

The Mountains and the Phantoms research-based series decipher the political and (post)colonial dimension of the natural environment in East Asia, drawing attention to its presence, self-healing and disaster that could resolve or exacerbate the devastating effects of geopolitical power struggles. The series includes the following projects- Can’t Live Without (2017), For Whom the Bell Tolls (2017), The Cold Mountain (2022-) and The Longing Park (TBC).

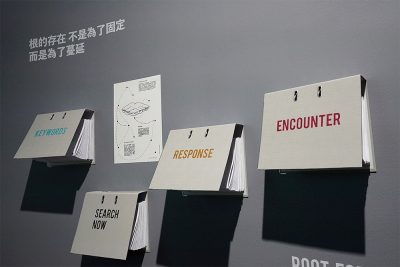

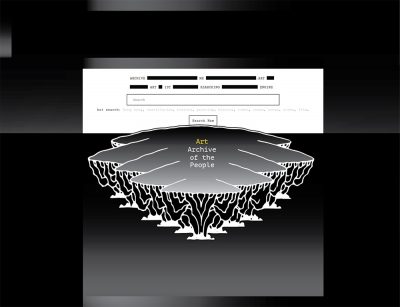

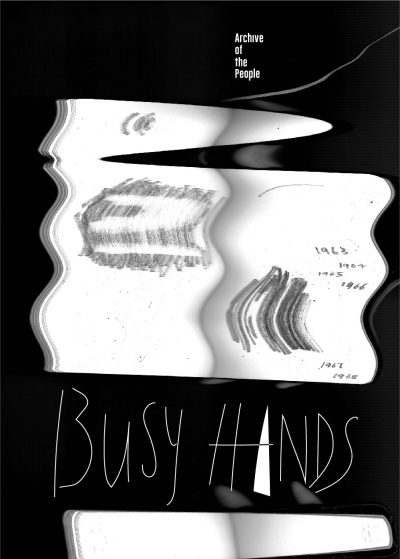

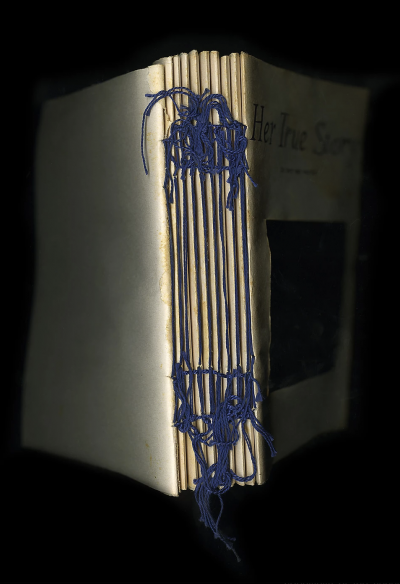

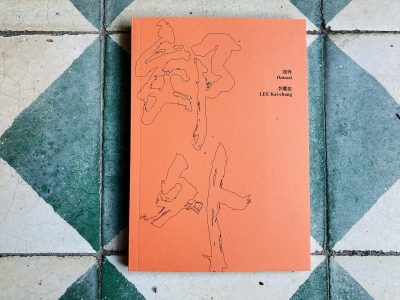

Lee’s ongoing research project Archive of the People addresses the political standing of documents and archives in the social setting. In 2016, Lee established the collective ‘Archive of the People’, which serves as an extension of his personal research to collaborative projects, education and publications.

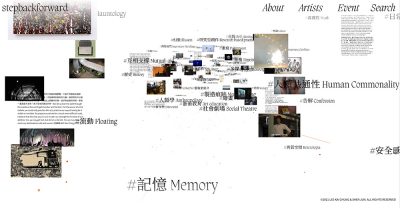

In collaboration with curator Shen Jun, Lee founded stepbackforward.art and The Phantom Archives in 2020 and 2022 respectively: the former is an online platform collecting artist archives, fragmented thoughts and artist methodology; the latter extends Lee’s Displacement series to a public domain, constituting an online archives that embraces public participation.

Lee was awarded the Consortium for the Humanities and the Arts Southeast England (CHASE) doctoral studentships from the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), and the 18th Busan International Video Art Festival <Selection 2024> prize in 2024; Honourable Mention in Sharjah Biennial 15 and Taoyuan International Art Award respectively in 2023; The Robert Gardner Fellowship in Photography from Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of Harvard University in 2022, he received Altius Fellowship from Asian Cultural Council in 2020; the annual Award for Young Artist (Visual Arts) from Hong Kong Arts Development Council in 2018, and WMA Commission (Transition) in 2017.

Keywords:

Coloniality, Affect, Displacement, Artistic Research, Archives

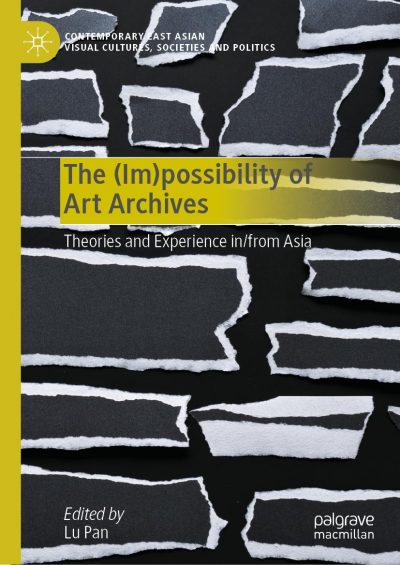

![The [Im]possibility of Art Archives: Theory and Experience in/from Asia (2023) The [Im]possibility of Art Archives: Theory and Experience in/from Asia (2023)](https://www.leekaichung.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/ArtArchives_01-400x268.jpg)