遷移/錯置 >

通向深海的狹道(2019-20)

《通向深海的狹道》旨在探討於二次世界大戰期間,在香港、中國大陸及日本三地遭受戰爭逼害威脅下促成的人口遷移。

項目以眾所週知的歷史事件「南石頭大屠殺」為主軸,在1942至 1945 年間,香港占領地總督部以不同理由將香港難民驅逐出境及遣返回中國。當時約80萬難民到達廣東(即現廣州市),並被關押在南石頭難民收容所,被迫接受了一系列人體實驗和細菌學測試。

藝術家通過文獻、田野考察及訪談等的研究方法重新探索這段歷史,再以影像、展演和雕塑等藝術創作回應,希望呈現主流論述以外的故事,對既有的歷史判斷叩問,同時發掘潛藏於內心的人性。

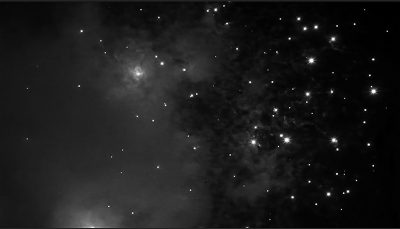

透過自述的方式,項目以藝術家90年代中學寫生課的記憶為開展。當時的美術科老師從儲物室取出了一個真人頭骨作教材。頭骨暗示了學校在日佔時期被徵用作第四陸軍醫院的往事,以及香港如何成為容納受傷士兵的後勤,研究應對東南亞傳染病解決方案的地方。1938年廣州淪陷後,大量來自廣州和華南其他城市的難民湧入香港,在短短幾個月內,城市人口增長至接近160萬。及後香港亦相繼淪陷,1942年始,占領地總督推出「歸鄉政策」,目的是將香港人口減半,以節省管治成本及減低對食物和水的需求;結果成千上萬的香港人被迫或被誘騙到廣東省各城鄉,部分被關押於珠江口的南石頭難民收容所。其後,華南防疫及給水部隊,另名為「波8604 部隊」對難民進行了各種的活體測試及生物化學實驗。在囚禁難民期間,因為各種實驗耗費大量細菌與病原體,波8604 部隊多次向陸軍中央要求補給。藝術家重返前帝國陸軍軍醫學校原址,即戰時專門研究、生產與供給各防疫及給水部隊的本部,現戶山公園進行展演。透過數小時的體力勞動,重現戰爭中的戰俘與難民強迫參與自掘墳墓的勞力,並內化暴力背後不同角色的潛意識。湛藍的帆布蓋過凹陷,隨時間的遷移承載著雨水及泥塵,漸漸成為公園的尋常景致,如同屍體投進化骨池,湮滅後成了海的一部份,浮沉浮載。

在懲罰與暴行的背後,創作串連個體與被遺忘的小眾,當中夾雜著不同的人性、心理狀態與為求生的掙扎。難民收容所成為了拘留難民的場域,進行實驗和收集研究數據的地方,亦是前途未卜的境地。

研究

就是無法回來的意思

就是無法回來的意思

一個關於「海」與「離散」的研究(節錄)

文:李繼忠

[…]

戰後——關於遺迹與保育

廣州市文化局於2002年9月1日公布日軍「日軍華南防疫給水部粵海港檢疫所」被列作「廣州市登記保護文物單位」(C W84號),那正是1941年4月,日據時期的廣州市工務局收南石頭部份土地 設立粵海海港檢疫所 ,亦是唯一一座南石頭事件中被評級的歷史建築,但至今仍然有六座建樓物有待被考古評估。2017年2月22日,中國文物保護基金會 代表曾到南石頭進行考察,並宣稱考慮籌集資金進行保育與城市規劃。同年3月 ,全國政協第十二屆五次會議中有23位政協委員提案,建議「建立廣州南石頭侵華日軍細菌武器大屠殺受害者紀念碑與紀念館」,並決議盡快「保護遺址與建築,分期分步籌建紀念館」。2年過去了,當我在2019年底至2020年到南石頭進行實地考察時,難民所遺址四週圍上鐵線網,裏面原有自行車廠的建築物除了圍牆外,基本上全部被拆除。難民所遺址附近亦未見有「歷史建築掛牌公示」和「保護文物」 等標示,個別建築物因日久失修而開始出現倒塌危機。例如:檢疫所建築主體日久失修,頂部因為颱風和天雨關係受到嚴重破壞,內部天花有漏水跡象。而且建築的部分被塗污、破壞(如門口頂部天花有焚燒的痕跡)與拆除。正門兩側以及門前的兩條石柱上,都塗上文革時代的共產主義語句,以及正門天花上仍殘留所有日文的標貼,理論上應該以一個歷史建築物的歷史整體性來完整保育。在1994年時,第二層的所長室還在。此外,建築前的架構與道路被佔用並改作當地的南河道派出所,檢疫所的空地興建了斜路導向山崗上的民居。以保育來角度,建築的整體脈絡被破壞與中斷,因為香港難民上岸後,必先到檢疫所進行初步檢疫,其後再分流到難民所、其他部門或直接釋放。因此,根據來自順德的梁先生 所繪畫的地圖,檢疫所亦稱「上所」,而「下所」則在西面的另外一個檢疫所,現在是民居。「上」「下」之區別可以是地理位置,也可能是難民進入南石頭的次序,因為日語中的「下所」有「下一個場所」的意思。據譚教授稱,在2016年他與志願者及工程師到檢疫所勘察後,覺得建築物有倒塌危機,所以敦促文物部門去維修檢疫所建築物,之後據悉批下大概十萬元人民幣左右的經費。但遺憾地時至2020年相關部門仍未進行維修。

另一個跟事件有關的文物——「粵港難民之墓紀念碑」處於南箕路旁一個安裝了上鎖金屬大閘的社區中,非居民無法進入。小區門口亦欠缺指示牌。紀念碑四週的公共空間被居民佔用放置雜物,成為私人空間的延伸。紀念碑的後方安裝了不同中共歷史脈絡的敍述展示板,但玻璃後塞滿了垃圾,可見沒有人維持整潔。

至於其他懷疑是二戰的歷史建築群,例如粵海港檢疫所和南石頭村西北方,譚教授所推測是「檢疫隔離」建築群、南石頭難民所廚房以及山崗(原日本山)上的被塗上紅十字的醫務所等等。現有的參考資料主要來自90年代初附近居民與前難民的訪問,現階段只靠社區脈絡、當時日本人就難民所的部署等因素作出合理猜想 。在新中國成立後,該區分別有廣州自行車廠與廣州紙廠宿舍建設項目,同時村民亦有佔據和作出不同程度的僭建或修改上述的建築物的做法 。

各研究者或關注事件的人曾多次向廣州市政府提出保育南石頭以及宣揚這歷史事件的建議,甚至亦聯同合作單位構想一個以「南石頭屠殺事件」的博物館與主題公園園區,但後來因為自行車廠清拆、土地業權以及廣東市政府想把那片原工業用地作商業用途等等的問題,以及2020年的疫症,建議就不了了之。

現在的難民所原址被規劃給前瞻產業研究院旗下的「南石28創意園」,而前瞻產業研究院 號稱是一間跟政府、學院與企業三方合作,致力發展企業與地產規劃與大數據研究的公司,同區中「31路攝影創意園」已經開始營運。原本是上所或日本山位置現在仍是民居,南石西小區主要是戰後定居的居民、工廠員工以及從事回收業務的人士。洗木池的對岸則仍然是工廠。南石頭北方的太古倉與大阪倉一帶已成功由貨物轉運站轉型活化作康樂文娛區,週邊一帶地段也如雨後春筍一樣建築民用屋苑、酒店、商場與商業大廈。這一種仕紳化的傾向很有機會和南石頭一帶蔓延;企業如前瞻產業研究院開發原本專門開發輕和重工業地段,現在轉移至開發文化藝術工作室與科技研究室。如果市政府把具有珠江口岸風景的南石頭開發成純粹保育和紀念戰爭歷史的博物館區,而放棄發展成為集各地產項目和商業發展於一身的多功能區域,而在現時中國大陸的發展脈絡中,個人認為那機會較低。另一方面,城市往原本是郊外的區域擴張是常態,而帶有歷史價值的地段,現在已有一大部分建有住宅高樓,試想想,如果難民所與屍體發現的事件被包括在博物館的論述,房價難恐會受到嚴重影響。因此,在這一個時間點上,保育與地區發展成為了矛盾,企業、財閥與市政府之間的合作(或角力)漸趨明顯。

至於在政協第十二屆五次會議中提倡『市文化、文物部門可牽頭開展現場有關文物的考古勘探』,必然牽涉相當大的難度,原因在曾掘出骸骨的南箕路一帶,現已發展成不同小區,若然要進行勘察的話,必須跟小區居民與管理長期協商並達成共識。如果是在南石頭難民所遺址,難度相對較低,因為遺址中的自行車廠已被清拆。不過,我在2020年初觀察到在遺址中有人駕駛大型機器開始全面清理瓦礫,推測是準備建設,但未知是私人財閥還是市政府。若果建設工程一但展開,即使有新的考古發現,恐怕透明度會是一個重要保育因素,否則發展商為了不阻礙工程進度,會把發現隱瞞,因為一但發現骸骨,恐怕會影響日後地產項目的聲譽和利潤。

以上都是關於硬件的問題,如果要進一步推進建築群的保育,無論是物業的地契、業權、建築物的結構等進一步研究都需要從官方資料與邀請歷史學家與考古學家進行進一步考證,隨之而來,就是啟動向居民諮詢、研究收地再勘察。不過,政治因素與地方權力角力比上述更關鍵。

至於軟件與公眾教育方面,自90年代始,一眾地方教育工作者與保育人士亦進行過訪談一對象主要是圍繞著附近居民。但我認為需要更有系統和縱貫研究 (longitudinal) ,第一,必須要向現仍在生的廣紙與自行車廠工人進行訪談;第二,與當地村民以及難民所的生還者進行訪談;第三,正正現在我這個項目進行中的部分——透過社交平台與本地人脈,向廣東與香港公眾進行公開徵集 ,以求尋找所有當時曾經被遣返的香港難民、他們的親屬和第二或第三代。據馮奇所述『在1945年日本投降前,國民黨快要接收難民所時,當時難民所剩下的難民很少。香港來的難民所剩無幾。幾千難民就此四散,不了了之。 』,加上香港難民在戰後有機會留在廣東省甚至中國大陸其他城市定居,所以第三部份是很多不穩定因素,相對需要較多人力與時間。在公開徵集中,我主要關注是死傷者的身份,以及遣送到廣州的香港難民的在地後續生活。

[…]

是自去年開始疫症蔓延,在某程度上跟南石頭事件產生更強烈的連結和共情,即使我和其他人所感受的,遠遠不及當時難民所受的萬一。是次項目的作品曾在不同展覽和場合中展出過,每次我總想找出在當地展出的理由。在黃邊站當代藝術研究中心展出的除了是一個記憶碎片中殘留的場景,亦引領觀眾與参加者進入公共項目——分別是一個叫「海邊散步」的行走項目以及露天放映,後者令我再一次思考作品對於當下和在地性的意義。令我深深感動的,莫過於在難民所原址放映作品。事前沒有太多預設,例如村民怎樣看待「藝術作品」,還有能否解開「歷史的謎團」。在放映期間,銀幕前坐滿了年輕的觀眾,一邊有村民在七嘴八舌討論祖輩怎樣挨過佔領時期,年紀老邁的婆婆在來回溜躂、放狗的村民站著看影片,另一邊廂有神情嚴肅的街道辦事處職員到場不斷拍攝:他在留心錄像內容的同時,也分心看看觀眾反應。錄像作品的獨白與聲效混合了遠方珠江上的運貨船鳴苗聲,以及工人正在修建觀眾背後的功德祠。也許,我不能冀望一個項目就能一一梳理歷史複雜性,也不指望在研究過程中的「新發現」能發人深省;但把作品帶離習慣的藝術場域,為它加進了生活感與在地性,把作品與現實重疊,至少可以開啟跟不同種類的人對話的可能性。

在項目中曾訪問過一位93歲的老太太,她曾經歷過難民所、抗戰勝利、國共內戰、新中國、公社年代等等,我亦把她和訪問內容轉化成戶外放映中展示的作品——《通向深海的狹道,第五章:長夜將盡》(2020)。令我印象深刻的,是在訪問和交談中,她總表示出深深刻印在腦海的,不是戰爭中人浮於事的苦,而是在往後80年間,她如坐在顛簸起伏的小船上亦處之泰然,社會福利制度是她心之所安,那正正是她的「真實」,而不止是檔案中記載的數字與事件來龍去脈。

當不同的藝術家一直希望作品不要給歷史一個定論,因為我們總相信藝術所帶出的想像對於現實生活更有創造力,觀眾可以自己去完成留白的部分。跟同行的藝術家朱建林討論到這方面時,提及年輕一代可能面對那個「想像空間」時,也力不從心去填補和創造,因為多年的權威性的教育和社會制度框架令到產生「想像」的機制、語彙、技巧都缺席了,那亦是本節初所提及到歷史研究中批評式思考的根本之一。在黃邊站的一場分享會中,有一位朋友提問:怎樣延續這個項目?或許藝術家可以透過創作在知識層面上推廣歷史的兼容和創造性,就如上述對於歷史與當下的梳理和批評;此外,筆者還深信,藝術作品的感受性可以超過理性思維和語言,在了解苦難後對世界更加關懷,那股微光可刺激人性中對善性的追求。

(文章寫於2020年6月。2021年2月修改。)

文章刊於《郊外》(2021)

評論

”你看見穿過草地 從霧中飄來的死氣了嗎”

“你看見穿過草地

從霧中飄來的死氣了嗎?”

文:張煜航

在宮崎英高製作的電子遊戲《黑暗之魂3》中,「吞噬神明的埃爾德里奇」預見了深海時代的到來。在遊戲中,深海時代(被隱晦的)描述為,寂靜無聲,所有生命都將回歸靜止,被「幽邃」統治的世界。

深海,是法西斯美學的極致。暴力的至高性和宿命實則轉向了細膩,綿長又幽深的沉默。黑暗之魂中的怪物幾乎都一言不發,Aleksandr Sokurov的天皇[1]的日語詞句不傳達任何信息。而一進入展廳,《吸煙的女人》沉默地吞雲吐霧。她精緻的短髮裝扮是為了面對不可預知的命運,而正是這一點出賣了她。與其說逃避危險,不如說她本身就是那至高暴力性的餌食物。流放的難民、集中營、Unit 8604[2] 的細菌實驗,必定需要一個吸煙的美人來完成「撒馬爾罕的死神」[3]中,受害者與迫害者共謀的誘惑,而世人誤把這稱作命運。

然而,我們不能讓陳舊的浪漫主義慾望生產來為法西斯美學買單。事實或許恰恰相反。冷戰時期的航天器來源於古希臘的飛天壁畫和密教咒語,而那三條「通向深海」的狹道,實則是戰時日本將整個東南亞(包括嶺南地區、香港、台灣和馬來半島,其實這一點從英殖時期就開始)作為戰備和物資中樞這一巨大系統中的短小通路。而香港,無論作為英殖時期的「東方之珠」,還是作為90年代賽博之愛中生冷而曖昧的迴路的中樞,抑或是如今「送中條例」中被强權挾持的逃逸者,都是那個通路上的「美人」,散發著致死的誘惑。只不過,體系和計劃的模型,比真實還要真實,現實的底色一步步加深,運轉的極限就是純粹的黑色;桃花源總會轉變成幽暗的「深海」,整個系統的廢物處理中心最終會吞噬一切。這就是為什麼,《挖掘工》印證了古老的煉金術箴言:As Above, So Below。死亡的物流鎖鏈飛升,海底築起反轉的宏偉都市。深海是物質,是堅硬而混雜的物質。機械又重複的消耗,那是在海底作業的身影。

日語的特性,是可以在傳達信息的同時將其消解在空無一物的基底上。無論是南石頭集中營裡的難民的歌謠(《演歌歌者》)還是《佐治與游泳池》中,那個在戰後廣州軍事法庭中為自己辯護的日本兵,蒼白又堅定的言語,它們所傳達的,彷彿都消散在展廳的高高低低的磚牆旁,反襯了那頭骨與游泳池黏著的無言。《佐治與游泳池》與《郊外》中,藝術家的話語同樣清晰和精準,幾乎到了「黏膩和眩暈」的程度,我们不禁懷疑,《郊外》的獨白是否是生物發出的聲響。

《黑暗之魂3》中,埃爾德里奇靠著吃人(最終發展到吃神)來企圖存續於他所預見的深海時代。漸漸的,他擁有了他所吞噬的人和神的思考與記憶。殊不知,他正是因為無盡的吞噬,使自己變成了幽邃的一部分而Unit 8604在南石頭的化骨池,也像藝術家說的『被人的身體所造就,成為了深海』。

『你看見穿過草地

從霧中飄來的死氣了嗎?』[4]

-Robert Walser

[1] The Sun, 2005, 亞歷山大·索科洛夫 Aleksandr Sokurov

[2] Unit 8604為侵華戰爭時期日軍的廣州第8604部隊,被認為在當地進行細菌戰與人體細菌實驗,《通向深海的狹道》系列中所提到的南石頭難民營被認為與其細菌實驗有關。

[3] 取自美索不達比亞古代傳說。講述一個士兵中午在市場的拐角處碰到死神,而且似乎看到死神向他做了個威脅性手勢。士兵嚇得趕緊跑到王宮裡,要求國王給他一匹最好的馬,趁黑夜逃避死神的追趕,跑得遠遠的,遠遠的,直抵撒馬爾罕。聽到這話,國王便將死神傳呼到王宮,責備他恐嚇了他最好的僕人之一。然而死神感到很詫異,便回話說:我沒想嚇唬他呀。在那裡見到這個土兵,我也很吃驚。事實上我們的約會是在今晚,在撒馬爾罕。

[4] Walser, Rober, Oppressive Light: Selected Poems by Robert Walser, Black Lawrence Press, 2012.

看到歷史中“被不測分割的人們”

看到歷史中“被不測分割的人們”(節錄)

文:張子木

還記得2020年11月份在WMA展覽時他組織的“海上顛簸”活動,行前沒有告知任何項目的信息,只有簡單的海上安全規則。隨船的幾位剛好都是女性,大家戴著口罩,安靜的坐在船內一角。一個半小時的旅程,視野只見海水與周遭漸漸陌生的香港海岸,唯一熟悉的是顛簸的姿態,和體內漸漸湧起的一些酸澀的氣息。我帶著對於展覽的預設,起先覺得這是一次“體驗”之旅,體驗被迫遷徙的難民在海上的一小段旅程,一種道德性的曖昧與無所適從佔據了前半段行程。但在船只返航之後的隨意攀談中,我才知道個體間的感受是如此不同,一位剛結束酒店隔離的外國女藝術家感到的是莫大的解放與舒暢。我雖帶著一些思考上的包袱,但在無任何框架的行程中,還是看到了很多意外的景象,像是一只跨海奮飛的蝴蝶,防波堤上的陳年小廟,紮帳篷釣魚的人⋯⋯ 這些細處都是所謂“重返”,“體驗”等僅從外部去框架性解讀這一活動所無法化約的。阿忠用文字、聲音和影像紀錄了每一次的航程,參與者對於行程的感受。這些紀錄想必也會融入之後的展覽,成為生成中的“人人檔案”。

在尋跡檔案史料,親赴歷史地點之後,阿忠所做的並不是將歷史數據可視化,抑或是企圖去追責和控訴,而是一種可能更艱難的以自身軀體與感官為幕布的投射與演繹,繼而發生共情。雙頻視頻《長夜將盡》編織出兩個南石頭難民營親歷者的彼此慰籍,舌頭被一節一節砍去,皮膚被慢慢燙萎,被沾染瘧疾的蚊子叮咬⋯⋯戰爭的瘋狂以科學的名義被冷靜的執行,被拋置其中的兩個裸命在他的想象中仍有機會相遇,在徹底被碾碎之前也會看到新年的煙花,獲得片刻的釋放和超脫。與愛國主義情懷中大肆渲染的激情向死不同,阿忠所看到的是苦難中仍留存的一種柔弱但堅韌豐富的人性與人情。如果說戰爭是一種非人化的手段,流行歷史影視劇則是一種對英雄與敵人的超人化的描寫,阿忠的影像書寫將歷史文獻中碎片化的線索重新搭建為一個日常的劇場,登場的陌生人,無論身份,都是有豐富情感與感知力的,是可以與當代都市觀眾進行隔空對話的。

線上旁聽黃邊站的討論時,聽到觀眾對於這種工作方法的倫理性的疑慮,阿忠的回應是他相信個人化的感受與動機,看似客觀的數據與描述,並不能使我們接近一個活生生的人。這也可以聯系到我們是如何理解“共情”的。學者Hans A. Alma 和 Adri Smaling(2011) 認為,真正的共情,並不是純粹的心理認同與身份換位,因為一個人總是沒有辦法真正的完全換位、經歷另一個人的情狀。所以他們提出,最理想狀態下的共情應該是基於個人的想象力去體驗另一個人所處的經驗世界,同時加入自己的經驗特別是情感 (p.203-204)。我在阿忠的作品里便感受到了這樣的共情,當提到實驗中的灼燒時,他拍攝自己布滿紋身的手。煙花的元素有史實所依,也源自創作期間他在日本駐留所看到的夏日煙花,與揮之不去的新聞畫面中香港街頭的催淚彈煙霧。此外,藝術家也以自己的身體置入一種歷史再造的場域去感受與行動,在錄像《挖掘工》中,他去往東京新宿戶山公園, 當年731部隊體實驗室的其中一處遺址,在公園路人的矜持或漠不關心中去自掘墳墓,像許多難民曾被迫做的那樣。當我們透過屏幕觀看,我們情緒上所更接近的,是歷史中與現實裏的旁觀者,還是被迫執行此任務的人?這是阿忠作品裏面的開放性所在。此次展覽將他自身在疫情期間的隔離經驗融入到對作品的重新放置,也是一種對自身身體經驗的敏感,持續性地踐行由己及他的思考、工作方法。

學者與策展人Jill Bennett (2005)在一本研究關於創傷與藝術的書中寫道,這類藝術創作是交換性的(transactive),而不是溝通性的(communicative)。“我們會被觸動,但並不一定知道個人經驗的‘秘密’ ” (p.7)。阿忠作品的特別之處還在於對這種“交換性”的進一步玩味,讓極具張力的身份在一個模糊與曖昧的時空進行交疊。《演歌歌者》由曾參加日本學運的日本老人將南石頭難民營流傳出的打油詩唱成日本傳統演歌,《吸煙的女人》讓日本友人演繹戰時年輕香港女子,在剪髮扮成男裝逃難之前抽最後一根煙。在這些打破時空、地理邊界的演繹中,牢固的國族身份、身體政治與觀看時的共情投射都變得流動起來,各中矛盾卻又真切可見。

這一系列作品創作的年份,2019到2020年,時值全球社會運動高漲與新冠疫情肆虐,社交媒體上充斥著各種對戰爭的想象與臆測,邊界和身份屢屢成為社會事件的觸發點。圍繞廣州南石頭難民營的敘事,也可以置入有關“香港人”身份邊界變化的歷史敘事。南石頭難民營的建立源於二戰時香港人口的暴增,廣州被日軍占領後,大量廣東難民逃入香港,資源緊缺。日軍企圖減少香港人口便出台歸鄉政策,將50-80萬身處香港的難民,包括部分祖籍在廣東的香港原居民,以欺瞞的手段遣返回鄉,不少人喪命於途中的汪洋大海和廣州的南石頭難民營。在香港展覽時,幾篇展評都將這批歷史難民直接寫作“香港難民”、“香港人”,其中一篇也和香港的反送中運動相關聯,形容是歷史上的“送中”,卻並不計較事件中的身份與邊界錯位,對比當下粵港兩地的一系列討論,非常耐人尋味。阿忠在採訪中也不諱言歷史中的暴力遷徙與當今香港的飄零對他創作的啟發。這種映照不是線性的歷史對比,而是不斷的開辟出順滑敘事的岔路。

重新回想我在“海上顛簸”活動中駛出西灣河碼頭,進入南中國海域的過程,直到看到有中國國旗的船只駛過才意識到或許某個浪頭之中我們已經“越境”,跟著錄像中日本/香港/廣東女子吐納香煙之際,我感到的是作品對於地理戰爭和肉體戰爭等對立二元性的拒絕,面對歷史的廢墟與卷土重來的人間爭鬥,任何邊界分明的的敘述都恐怕是無力且徒勞,但以藝術作為越境、穿梭時空的共情技術,以肉身再赴“通往深海的狹道”,是可以讓我們看見那些曾經“被不測分隔的人們(those who parted by unexpected fate)”,一如阿忠在作品中寫下的。

參考:

Bennett, Jill. Empathic vision: Affect, trauma, and contemporary art. Stanford University Press, 2005.

Alma, Hans A., and Adri Smaling. “The meaning of empathy and imagination in health care and health studies.” International journal of qualitative studies on health and well-being 1, no. 4 (2006): 195-211.