Displacement >

The Retrieval, Restoration and Predicament (2017-20)

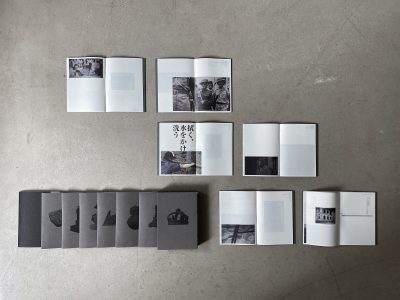

The Retrieval, Restoration, and Predicament is a research/creative project. Through studying historical records and objects of Hong Kong during the last years of the Second World War, the project investigates the transition of meanings of a ‘memorial bronze statue’ brought about by the passing of time. The series of creative works, consisting of videos, sculptures, and photography, asks a number of questions.

In addition to its spiritual and symbolic meanings, how does the essence of the ‘memorial bronze statue’ evolve over time? In early 20th century British-ruled Hong Kong, colonialism manifested itself through the proliferation of bronze statues. After going through the Second World War, and the social movements of the 1950s to the 1980s, and finally the Handover, these statues have gradually become reminders of the colonial era for the proletariat. When the statue is placed in a public space as an ideological manifesto, what sorts of social discourse develop relating to the intertwining relationships between ‘the object’ and ‘the people’ in the space? If the monumentality of the statue is dependent upon the permanence of its materiality, how does the symbolism of the statue respond to the physical and spatial transitions it experienced through the Second World War, post-war and post-colonial periods?

The Imperial Japanese Army occupied Hong Kong from 1941 to 1945. In order to satisfy the material needs of total war in Greater East Asia and the Pacific, a ‘copper collection campaign’ was launched on the Home islands: to get the public to contribute any metal that could be melted down and remade into weapons, including household utensils, metal components of clothing and footwear, streetlights and lampposts, railings, temple bells, statues of gods and heroes, etc. At the same time, the Imperial Japanese Army confiscated 11 bronze statues from Statue Square in Central, Hong Kong. In August 1945, when Japan surrendered and the war ended, the British government of Hong Kong was notified by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) that four statues – Queen Victoria, two HSBC lions, and Sir Thomas Jackson (Chief manager of HSBC from 1876 to 1902) – had been discovered. After their return to Hong Kong, however, the statues were mired in a situation of restoration and predicament. This is the background in which the works in this exhibition were created.

Unfortunately, the documents pertaining to the statues’ history, like the statues themselves, are scattered and inconstant. A portion of the records and primary source materials produced before and during the war were lost in the bombing of the UK and the Japanese Home Islands. In addition, after the Japanese surrendered, they destroyed many files in Hong Kong to keep them from falling into the hands of enemy forces. But Hong Kong’s post-war archives were relatively intact, including conversations between officials, documents such as applications for funds from the colonial government to the British government, etc.; as for secondary source materials, such as newspapers and propaganda publications, there are discrepancies both because of wartime disruptions in the flow of information, and the spin each power puts on its propaganda.

For the purposes of academic research, I concentrated on the primary sources, supplemented by secondary sources, but for the purposes of artistic creation, the latter provides imaginative space and period texture. The ‘people’ from history have disappeared, but the traces they have left behind on the ‘things’ can feed the creative process, because they are the best evidence we have for the existence, speech, and behaviour of the ‘people’.

The people involved in this wartime story all tried to rediscover some things, to repair and restore an earlier situation, but couldn’t help, for a variety of reasons, falling into a predicament they could not get out of. My role in this project is also part of this cycle: retrieve (lost files and history) > restore (history and the original appearance of the statue) > become trapped (in the present context and system). ‘Archives’ are not just a record of what happened. Whether and how people can access the archives, and in what circumstances and context they can be read, also matters. I believe that the archival framework, system, and contents should be people-centred, and the participation of archive users can refashion the historical narrative.

As Boris Groys says, in modern society material trumps imagination, and people are too focused on ‘objects’ as evidence of the passage of time. We have expectations for ‘the future’; if we want to have a meeting tomorrow afternoon, we mark it in our diaries. For ‘the past’ we also have words, files, video, and images we can review. On the other hand, we are not necessarily able to fully understand, through the ‘objects’, the time that has been compressed into them. When I open a file, a gossamer-thin document may have a hundred years of history; the ratio of material to time is not constant. In this project, therefore, I hope to weave together the details from multiple historical narratives, unpeel the layers of accumulated incident, rearrange and reconnect them, and thereby illuminate the ‘present’.

Research

The Retrieval, Restoration, and Predicament: Objects, memories and records in wartime

The Retrieval, Restoration, and Predicament: Objects, memories and records in wartime [Excerpt]

Text: Lee Kai Chung

During the occupation of Hong Kong, a great deal of money was taken for the Japanese military in the Pacific and other theatres. So, the cash-strapped Hong Kong government, faced with an enormous cost for repair and maintenance expenses, appealed to HSBC Bank [1], which had paid for the development of Statue Square before the war, but HSBC was struggling with its own property damage and lost assets. […] After the Japanese surrender, HSBC staff found large quantities of property that did not belong to the bank or its customers [2], including gold and silver jewellery, military supplies, opium, etc. […] So, the government decided to sell these items through public auction [3] to raise money to rebuild public buildings and restore statues. However, another problem arose: not all of the items were suitable for public auctions, for instance left over military equipment (bullets, military equipment, guns), opium, etc. To take the latter as an example, it was sold through a semi-public auction to a Singapore pharmaceutical firm to make anaesthetics. In the end, part of the proceeds of the auctions went into a Special Revenue Fund to pay the costs of repatriating and restoring the statues.

In this short history and recollection of war, colonies, and former colonies, the bronze statue appears in different images and forms, and its movements and physical transformations form a perfect cycle – from the Japanese occupying Hong Kong and confiscating the statue, melting it down to make weapons to attack and invade other countries, to Japan’s defeat and surrender, the return of the statue to Hong Kong, the Hong Kong government gathering up and auctioning off the things left behind by the Japanese to raise money to restore the statue. At the physical level, this cycle is not just a record of the statue’s travels and the experience of regime change, it is also witness to the transformation of a symbolic representation, and how people face transition.

[…]

In the middle and late stages of the research, I finally obtained some relevant information from the British National Archives. In February 1947, Port Supervisor Mark Young, in a report to the UK Colonial Office, mentioned that the statues had been sent by the UK Liaison Missions from Tokyo back to Hong Kong [4].

Restoration – the damaged Queen Victoria statue and the lost blueprint

When the colonial Hong Kong government heard that the statues had been found, they did not take any immediate action. There are always many pressing issues and the return of some statues was not a high priority. According to documents from the UK Colonial Office , one of the main reasons for the delay was that the war had damaged and changed the landscape and buildings of Central District, and it was hoped that this could be an opportunity for another round of urban planning and reclamation works, a proposal for which was submitted to the UK in 1947.

Around this time, the Hong Kong colonial government established a temporary Public Monuments Committee, in conjunction with the Public Works Department and its Architectural Office. The Committee commissioned Raoul Bigazzi, an Italian sculptor who had set up a studio in Central in the 1930s, to research and remake the Queen’s missing pieces.

From the minutes of the Committee’s discussions, when the Queen’s statue was returned from Japan, every part of it had been cut away or damaged to various extents as follows:

1. Orb held in her left hand;

2. The crown on the queen’s head;

3. The sceptre [4];

4. The right arm holding the sceptre;

5. An imperial crown resting on the ornamental pedestal in the centre of the throne;

6. A lion on the throne;

7. A unicorn on the throne;

8. A pair of earrings;

9. A receding panel at the foot of the throne;

10. Two studs;

11. One side panel of the chair.

The Queen Victoria statue was originally designed by Mario Raggi [6], an Italian sculptor living in Portland Place, London, and cast by H. Young and Company, a foundry in Pimlico, before finally being officially unveiled in Hong Kong in 1896. Bigazzi asked the colonial government to ask the UK government for a production blueprint to use as a reference. Unfortunately, the UK government hadn’t had the blueprint even before the war, or it had been destroyed in the Blitz. The Hong Kong government commissioned the UK Ministry of Works to liaise with the sculptor, but in the end Raggi could not be found; according to the National archives, there is no shortage of documents and photos of Raggi’s commissions predating Victoria, so it is very strange that the British government didn’t put any blueprints, sketches, or minutes of any discussions between officials and the sculptor into the archives. The British government then asked the casting workshop for any copies of the blueprint, but unfortunately, the workshop had been destroyed in the Blitz, they’d moved to another location and dropped out of contact. For this reason, the Colonial Office proposed commissioning the Morris-Singer Company, who had cast the statue of George V in Statue Square.

After comparing the Hong Kong and UK archives, I can only conclude that the blueprint is lost, and Bigazzi was working from a number of photos from the UK Public Works Department of the Queen’s statue taken before it had been shipped to Hong Kong, plus his artistic judgement, to produce the new pieces of the statue. In addition, the written descriptions of the damaged portions of the statue in the Hong Kong and UK archives differ. This discrepancy in the historical narrative probably springs from the two regions’ differing images of the statue, as well as speculation by the British government based on similar images of the Queen.

In the middle of 1947, the British and Hong Kong governments assessed the costs and feasibility of the restoration of the statue. The British government asked the Morris-Singer Company for recommendations, and they offered two proposals:

1. Send the statue back to the UK for measurements, so the lost and damaged portions could be recreated in clay, then use the lost wax method to cast new parts, attach them to the statue and make adjustments.

2. Have the Hong Kong sculptor (Bigazzi) make plaster models of the lost and damaged portions, and send them back to the UK for casting.

From an artist’s perspective, the first option is the most appropriate, because the only way to get accurate clay modeling is directly from the statue; if the parts don’t match up exactly, they can be adjusted. The damaged or missing portions of the statue all extend out from the torso, and the ‘wounds’ were not tidy; if plaster casts were made in Hong Kong, and a British sculptor used the models and drawings to make and cast the pieces, it is possible that the pieces wouldn’t be able to join neatly to the main body.

In the end, the Hong Kong government did not pursue either of the above proposals, because the costs of the first proposal exceeded the budget, and the British government was unwilling to pay the full costs, while the feasibility of the second proposal was not guaranteed. Instead, they decided to commission the Hong Kong-based Bigazzi to make models. Regrettably, I have only found the exchanges between Bigazzi and the Hong Kong government at early stage of this process, and have no information to show that the items were cast in Hong Kong. Bigazzi’s studio was in Central, and a foundry for the statue would require sufficient space and ventilation, so I surmise that the government used a third party for casting, which may have been the Morris-Singer Company.

When I read in the files of the twists and turns in the ‘refurbishment’ part of the story, and the circumstances around the files, the order in which they are arranged, I feel that neither the process of ‘refurbishment’, the artist’s imaginings of the statue (in the absence of the original plan, Bigazzi’s individual creativity had to play a role), nor the opinions of officials and the public towards ‘refurbishment’ are adequately recorded. For this reason, in the absence of sufficient information (including the blueprint and the refurbishment documents), I tried to use my own methods to reconstruct the missing pieces.

[1] HSBC funded the construction of Statue Square and the production of some of the bronze statues in the square before the war.

[2] PAPERS RELATIVE TO AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE SEIZURE OF PROPERTY BY THE JAPANESE IN THE COLONY OF HONG KONG, 18.12.1945, HKRS165-4-1, Hong Kong Government Records Service, Hong Kong.

[3] In 2016, I researched and created a project called The Order of Things, relating to the history and process of public auctions, and the people and objects involved in them. The earliest record in the Hong Kong Archives dealing with public auctions is from 1886, when the Navy received a consignment of goods, and discusses how to convert it into cash through a public auction. Early public auctions usually took the form of public-private partnerships, wherein independent auctioneers were commissioned to conduct the auctions in official or non-official venues. The dates of the auctions were not predetermined, but depended on the quantity of the goods received. After the Handover, the Hong Kong Government Logistics Department has held regular public auctions since 2003. Items auctioned include confiscated and unclaimed goods, and unused tools and goods from various government departments.

[4] Hong Kong: Statue of Queen Victoria, Showing Missing Parts, 1947, CN 3/46, The National Archives, United Kingdom.

[5] According to the archives, during the restoration, the sceptre was possibly modelled on that of King Edward VIII.

[6] Photograph of a plaster cast entitled ‘Compulsory Education. A lady teaching a child, profile view, 2 June 1877, COPY 1/37/322, The National Archives, United Kingdom.

Review

Melancholy and Wishfulness in Historical Records

Melancholy and Wishfulness in Historical Records:

Lee Kai-chung’s solo exhibition ‘I could not recall how I got here’ [Excerpt]

Text: Vivian TING

Hong Kong is a city of amnesia. People would let historical monuments be pushed away by urban development because what they care most about is making a living, resulting in the destruction of relationships and communities built over time. Due to the lack of an archives law, the Hong Kong government has destroyed documents that would have been more than 130,000 metres long if they were lined up. Departments responsible for preserving memories, like the Government Records Service, always show a reluctant attitude towards any requests for archival records because of the official order, trying to draw a veil over their work. If all documents regarding Hong Kong vanish bit by bit, will we be able to recognise ourselves and remember what made Hong Kong the way it is today? What historic events can the archival records tell us about?

The word ‘archive’ connotes all kinds of ‘historic evidence’, including commercial contracts, legal papers, maps, building plans, oral historical records, news videos, three-dimensional architectural models and many more. In archival studies, ‘data’ of various materials and different kinds are sorted, organised and catagorised to preserve the memories frozen in time. The collection, cataloguing and documentation of data must comply with the regulations on work of the institutions they belong to and follow the logic of their academic fields. The attempt to get hold of the past in a disorderly myriad of things could show us the direction that we seem to understand and feel comfortable to move in.

However, a number of archivists point out that during the process of collecting documents, organising and cataloguing information and preserving records, it is not possible for the participants to take an objective stand, and therefore the records that are kept are definitely not conclusive ‘historical facts’ or simply ‘facts’. In recent years, there has been increasing concern about how the general public use the records in archival studies and about how archives have evolved into places dedicated to the production of knowledge and meanings. At the end of the day, if we just store materials and leave them in archives, what we keep is nothing more than meaningless disjointed information and all we have are merely superficially unrelated memories that we cannot probe into.

Lee Kai-chung thrust his head into piles of documents and studied them in an attempt to connect people and stories of different eras and to find out what the past means to us in the present. Sharing a similar aspiration as the historians’, the artist aims to understand the linkage between the past and the present through his study and reshape the narrative around a certain historical event. Nonetheless, he does not follow the practice of historians, who try to get close to the “historical truth” to comprehend the context of things that have changed and of those that have remained the same. The artist is in pursuit of the feeble glimmer of time—the sounds of life, hidden in the gap of time, flowing around the edge between memory and oblivion, unclear and puzzling, and yet implicitly expressing emotions and desires. After all has been said and done, he tries to capture fragments of the old times, recounting in his own artistic language the stories of ordinary people who struggled to survive through times of distress. His solo exhibition ‘I could not recall how I got here’ recollects the vicissitudes of life in wartime Hong Kong by comparing and contrasting the different fates of the Japanese War Memorial and the bronze statues of Queen Victoria in the 1940s, sharing his reflections on how to deal with the times and the collapse and malfunctioning of the system.

[…]

Who do Hong Kong archival records belong to? They certainly do not belong solely to experts, academics or researchers, but to anyone who wants to learn about Hong Kong. Some of these people were born and bred here, some are enthusiastic about the past and the present of this former British colony, and others probe into the intricate history out of astonishment at this city’s strong vitality. Lee’s creation reclaims control over the interpretation of archival documents with his own artistic language, capturing a wider imagination of documents and the history of Hong Kong. He says,

‘The “people” from history have disappeared, but the traces they have left behind on the “things” can feed the creative process, because they are the best evidence we have for the existence, speech, and behaviour of the “people”.’

Perhaps stories of ordinary people do not matter enough to be written down in history, but the artist believes that everyone’s experience can reflect different aspects of the times and debunks the myths that we have about the past, shaping the established narratives of history. By sorting out documents like historical photos, military papers and posters, he made a three-channel video to look back on how people overcame turmoil and how they understood the times they lived in, through the eyes of a military general from the British garrison in Hong Kong, a Japanese soldier’s wife and a tomb keeper of the Japanese War Memorial. His artwork, developed on the basis of negligible personal feelings and expanding to collective emotions of society, walks the fine line between fiction and reality as it provides alternative ‘historical text’ to discuss the dark age of Hong Kong, which is gradually disappearing into oblivion yet we dare not forget.

The artwork starts with a private letter written by a British army officer. The letter tells of how the secret information of the loss of the Queen’s statues in Japan did not match the local news report. The general had urged the military to open an investigation into the missing statues again and again, but yielded no results and had to let the truth descend into nothing. Indeed, only very few people can call the shots when facing the currents of time. A Japanese soldier’s wife who came to Hong Kong to visit her husband, just had to watch apathetically as her people were gripped by the fever of militarism while surmising the visible and yet unattainable distance to her husband. Left all by herself, she gradually learned to enjoy the cruelty of her surroundings. She would rather be ‘engulfed by the charcoal darkness, and it brought along a sense of intimacy with the fear.’ The keeper of the Japanese War Memorial, who was also living in the darkness, tried to convince himself that time is something that needs to be rapidly depleted. There is nothing wrong with being caught by the Japanese army and forced to perform hard labour; his labour served as proof of his usefulness. Nevertheless, he had no clue about what was worth safeguarding in the tower and could not understand the point of this violence and destruction.

In the past when we read about Hong Kong under Japanese occupation, almost only generalised descriptions like ‘devastation’ and ‘people were living in misery’ were used in the books to describe this dark gloomy period lasting three years and eight months. We still remember Japanese troops slaughtering thousands of civilians, people eating corpses and practising cannibalism due to severe famine. Forests were also cut down and copperware at home was seized as a result of the lack of supplies… And yet the artist chose to depict thoroughly unimportant people who were unable to defy time, contemplating how a single person could find a place in this abnormal world and live a ‘normal’ life despite the collapse of the system. The protagonists in their stories want to seek the truth, or yearn for a loving intimate relationship, or merely get hold of evidence to prove their usefulness. These humble wishes are just normal desires that make humans human, but in tough times they seem impossible and unrealistic. The three stories show the considerable impact society has on an individual’s experience, and it is hard to define what each individual experiences—loss of balance, helplessness, oppression, coldness, confusion and unease—all these cannot be explained by rationality and yet express the individual’s and even community’s emotions of life.

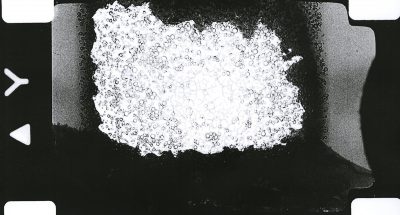

After all, works of art are different from historical accounts. Lee Kai-chung’s work can be taken as a modern-day fable, apart from being seen as an alternative kind of document. Scenes of a stopped clock, of the vast and boundless ocean and of overlapping shadows of flowers flash by in the video and imply that the perception of time varies wildly between individuals. During the passage of time, how are we supposed to make sense of our times?

The war made the Japanese soldier’s wife adapt to difficulties and disrupted the tender moments she had with her husband. She asked a mirror maker to engrave her husband‘s likeness on a mirror so that she could always see his face. However, the soldier had become estranged from her, and she could only wipe her mirror again and again, trying desperately to find the warmth that she used to feel when they were physically close to each other. As the reflection in the mirror replaced reality, what she saw was just an illusion. She no longer had the strength to return to reality and recognise the real situation. It seems that she had walked to the end of her small world even before it began. Just as she said, ‘I thought that flowers wilt slowly. And now I realise, they can die in an instant.’

The intriguing thing is that the tomb keeper read out aloud the newspapers that were still in print to pass his time, coldly watching the violent conflicts between countries. He had been confronted with dead people, seen the brutality and violence happening before him, and suddenly figured out that ‘when a system collapses, there will not be any difference between the good and the bad.’ Once the distinction between right and wrong is eliminated, the immanent order of a civilisation will become meaningless. Perhaps what he could not stand was neither the war nor the loneliness, but the long bleak life in which nothing was worth fighting for.

From the helplessness of the British military officer to the numbness of the tomb keeper and the desolation of the Japanese soldier’s wife, Lee’s video work collects fragments of autocratic violence during the Japanese occupation and of the perplexity of displaced people from his personal disjointed perspective. The monologues of the characters appear to be a chaotic mess, but they reflect the tedious monotone of the historical narratives on Hong Kong under Japanese rule with simple individual voices that penetrate grand narratives of national interests or the global politics. With the use of artistic imagination, the video recollects memories from the past with today’s experiences. So long as the story plots and recurrent scenes can be regarded as allegorical fables, the audience are free to assign contemporary meanings to the work based on how they understand the times and how they use archival materials. Perhaps this is the comfort the artist gives us. Time will pass, whether it is good or bad, but can we stand up for the values we believe in and respond to the challenges of our times? Although the war has been over for a long time, the tangle it created—how to deal with authoritarian oppression and how to comprehend the despair and resistance triggered by violence—is yet to be untied.

To meet the challenges of postmodernism, archival studies gradually shifted from work focusing on searching information to contemplating how to turn archives into sites for producing knowledge and meaning. What is the future for archival studies? Canadian archivist and scholar Terry Cook states:

Postmodernism requires a new openness, a new visibility, a willingness to question and be questioned, a commitment to self-reflection and accountability. Postmodernism requires archivists to accept their own historicity, to recognise their own role in the process of creating archives, and to reveal their own biases. Postmodernism sees value in stories more than structures, the margins as much as the centres, the diverse and ambiguous as much as the certain and universal.

The academic profession of archivists has emphasised the systematic collection and organisation of knowledge. In the postmodern era, special attention has been given to reflecting on the logic of the system, different narratives formed based on the data, and even dialogues with communities from different times.

Nevertheless, archival studies belong to communities. The ‘imagination’ that comes with archival records is not just about whether the building of archives involves different participants. Whether the building process can shed light on our thoughts depends more on how the contents of archival records assist readers in discovering the sense and sensibility of civilisations, and on the new interpretations added over time. Lee Kai-chung’s approach of using archival records does not only record stories of Japanese occupation, but also makes known his wishes for the future: searching for diverse voices of historical documents and stretching the imagination of Hong Kong and ourselves in the past. We look for information from the past, most likely because we want to find ourselves and recognition of what we have done. Thrown into a reign of terror, how should Hong Kong people recollect the past? How do we interpret our past to seek motivation to change the present?

Vivian Ting @ Art Appraisal Club

October 2019