Can’t Live Without(2017)

Single-channel video

16:9 | HD | Colour | 19’47” | Stereo

A Journey in Search for Discontinuity

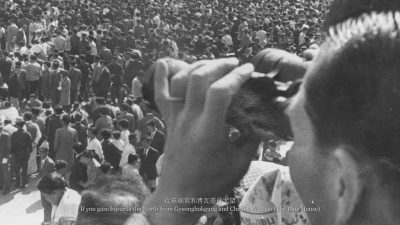

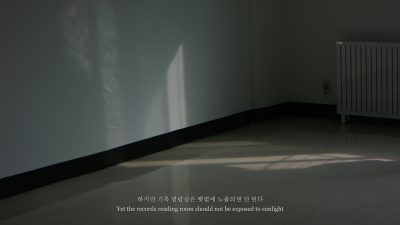

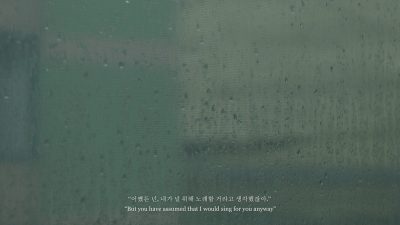

I sat in the archive reading room, waiting for the requested documents. The space was filled with a weighted silence, I could perceive the ringing inside my body. It recalled my memories when I sat on concrete pavement in 2015, listening to a waling song coming from a distance. Meanwhile, people were shouting in the direction of the sound. The nature and perception of the song were transformed over time during the movement, consequently, it intrigued my curiosity in the sonic quality of archival materials and their social relevance during my residency.

The aim of the project is not about creating a displacement of history based on my personal experience, artistic expression, and research, as it could not have my discourse validated within the residency period; nevertheless, to propose a room of historical plurality from a foreign eye, and believe in the inexhaustible generative power of archives. I want to look into institutional art archive within a museum context, and how it articulates meaning under its system.

In comparison with national archives or historical archives, contemporary art archives differ in their constitution, discipline, ways of acquisition, personnel in charge, subjects, etc. Though art archives do not diminish its social context or reduce the discursive space exclusively to artistic context.

Art archivists actively take highly individualized approaches to define their own domain of acquisition and categorization based on diverse fields of research, which reveal another dimension of art records in all kinds of context. Somehow art archives, in general, are highly institutionalized (i.e. the direction and nature of institute, which is not completely relevant to the quality of archival materials but creates constraint for the archivists), as a result, due to its unique and yet-to-be-developed practice, art archives in certain extent subvert the conventional top-down records generating system.

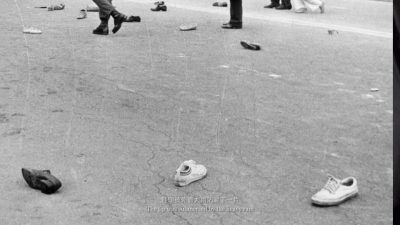

It comes to my major inquiry on the consistency of art archive practice, whether the archiving protocol is determined by the selection of archivists, or if there is freedom for creating social and historical discourse in the public sphere? In addition, how does “individual” matter to such discourse within and out of the national art institution? During the intermediate stage of my research, the notion of ‘public’ calls into question, I started to search for materials that were contributed by anonymous, or individuals who were often being categorized under groups, communities, or more formally known as, “Minjung” (民衆 /민중).

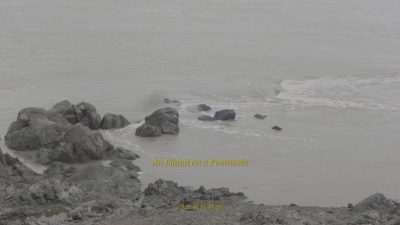

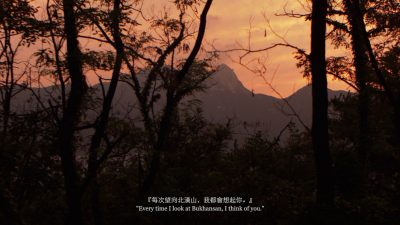

The film consists of narratives of three spectral entities, two females that deliver both monologues and dialogues, plus one male that remains silent but speaks through the archive. The phantoms or the narrators jump back and forth between the micro and macro narratives, and further cut through sedimentary layers of history. Their interactions begin with the geographical location of the artist residency, which recalls the shady artist’s memories on its practice of dealing with archival materials and archives; later, all three narrators trace separated events in affiliation with the archives. The nostalgic title “Can’t Live Without” alludes to the difficult situation of those three phantoms, who are no longer living but being trapped in an underground archive, and Choansan / Choan Mountain, in other words, their existence is bound with the archive.

Such highly subjective narratives somehow deflect the conventional authoritarian delineation by national archives. I articulate the historical narratives through curating alternative “truth” out of the existing archival apparatus. In comparison with traditional history, which is rigidly defined by persistent scientific archival practice, conventional documentation, and established institutional setting, the “discontinuity” or “incoherence” reminds me to conceive critically the historiographic disciplines in contemporary art.