The Shadow Lands Yonder (2022)

Septuple-channel video

16:9 | 4K | Colour | 24’30” | Multiple-channel audio | Japanese dialogue | Chinese and English subtitles

The Shadow Lands Yonder is a collaborative research-based work by Hong Kong artist Lee Kai-chung and Japanese artist Isaji Yugo.

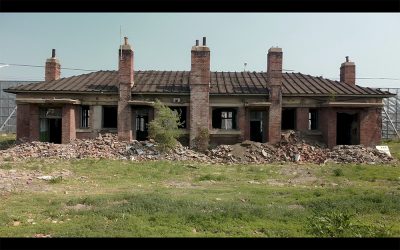

The project centers in Manchuria in the early twentieth century, a time of massive population displacement driven by war colonisation as the traditional empire collapsed and a new nation was created. The agricultural emigrates became an alternative instrument of colonial policy, developing a new world, making ‘home’ in a foreign land with fertile black soil, abandoning their origins and rediscovering their identity. The emigrates were trapped in a cycle of ‘longing – developing – leaving – stagnation – repatriation – being rejected’, their lives were drained in the shadow lands, while they had belonged to neither the country nor homeland that they longed for. Seventy years after the end of the war, apart from tracing the ‘human’ existence in space and material artifacts, the collective memories and consciousness, bodily experiences and affective heritage of ‘the struggle of leaving or not’ still haunt Dongbei (Northeast China) at present.

Methods

The two artists are unable to conduct their cross-border fieldwork due to the global pandemic; instead, they overcome geographical constraints, by adopting an alternate research methodology to conduct fieldwork and interviews in their own countries, and then share materials and exchange experiences. One of the main components of the project is the unfolding of former emigrates’ memoirs, followed by revisiting the routes they took to be repatriated back to their homeland, as if in augmented reality, to experience the overlap between the present-day Dongbei and the historical Manchuria. During collective research and creation, the two artists have diverse perspectives due to significant differences in language, culture and historical backgrounds. After much coordination and discussion, it becomes clear that the ontological differences are precious, as it was not dissimilar to the multiplexity implied by ‘Manchuria’, and so the rejection of homogenisation was retained in the work and writing as much as possible.

Historical background

In the early 20th century, the Manchurian belt was transformed from a grey area with many ethnic groups, tribes, warlords and powers converging into a multi-nation state, as a result of war and railway development. In 1932, Manchukuo was established under the auspices of the Empire of Japan. In May 1936, the Japanese Kwantung Army introduced the ‘Plan for the Agricultural Emigration of a Million Households to Manchuria’ and in August 1936, the ’20-Year Plan of a Million Households Emigration’ was formulated. From 1920 onwards, most of the semi-voluntary emigrants to Manchuria were railway employees, investors, military personnel and technicians, and after 1937, the top-down national policy of colonisation encouraged the agrarians, who were deeply connected to ‘land’, to leave their homeland and set off for unknown destiny.

Since the Mukden Incident (or namely 18 September Incident), Manchuria became the Japanese frontier and the rear of its warfare in East Asia. Under the national colonisation policy, the Japanese colonists were mainly farmers and grassroots workers, as Japan began its full-scale attack on China in 1937, Manchuria, as the breadbasket of Northeast Asia, and the mining, light and heavy industries that Japan was developing, provided sufficient food and supplies for the war in the Greater Asia. On the other hand, as Manchuria was geographically neighboured by the Soviet Union, although the main war zone for the Soviets remained in Europe, Kwantung Army created four barriers respectively for Manchuria as a precaution: natural barriers (mountains, rivers), artificial barriers (forts, walls, outposts), the Kwantung Army, and the Manchurian agricultural emigrates, the latter being the scarecrow in the Kwantung Army’s ‘Scarecrow Tactics’, designed to keep out the crows from the north if necessary. As it turned out, the Manchukuo officials and Kwantung Army fled to Tonghua, close to Korean Peninsula, before the surrender of Japan in 1945, and the emigrates were abandoned, or ordered to resist the Soviet Red Army through suicide-attack.

The identity of the agricultural emigrates would not have been ontologically transformed by emigration, as Japanese nationals had been living in a ‘nation-state’ at the time, while Taiwanese, Korean, Manchu, Mongolian and Han Chinese in Manchukuo were treated as essentially subordinate to the empire. The identity of settlers, who were under the semi-compulsory national policy in 1937, was ambiguous until the end of the war and even after their return to Japan – despite the founding slogan of ‘Five Races Under One Union’, there was a clear-cut social hierarchy in Manchukuo, with Japanese nationals officially referred to as ‘mainlanders’ to distinguish them from colonial immigrants from Korea and Taiwan. Japan, Taiwan and Korea had their own Nationality Laws, and there was no consensus in Japan on the Nationality Law of Manchukuo, so it had not been legislated by the end of the war. The settlers from Mainland Japan retained their original Japanese nationality, but some had dual Japanese and Manchurian citizenship in exceptional cases. As a result, the Machu-Japanese settlers had to go through a compulsory process of ‘identity transition’, especially in the case of the agrarian settlers who are the subject of this project. This is the major difference between the spiritual and psychological understanding of ‘Motherland’ and ‘Home’ in post-war repatriation.

After Japan’s surrender in August 1945, followed by a repatriation policy for the Japanese in Manchuria, which was led by the Kuomintang government with the assistance of the United States from 1946 onwards.The former Manchurian nationals were not able to resume to their pre-domicile status after their return to Japan and became second-class citizens, they were criticised morally and discriminated, considered to be profit-minded, but returned home to take refuge after the country’s defeat. After the war, the US-led Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) in Japan issued a population policy to expel non-Japanese nationals (i.e. former Japanese colonial nationals) out of Japan, with the aim of making Japan a mono-ethnic country. The repatriated Japanese from Manchuria were put in an awkward position in terms of their identity and social status, and their post-war social welfare was not comparable to that of local Japanese.

Nevertheless, identity recognition is not as black and white as legal paper, and such ‘identity transition’ is a complex process. The above detailed historical context helps us to reconstruct the psychological state of the settlers and repatriates at that point in time, when they were trying to adjust to the transition of multiple identities.

About the artwork

Focusing on the history of the Japanese evacuation and repatriation during the Manchurian period, the video and sound installation in The Shadow Lands Yonder is a collaborative research project between Lee and Isaji.

Based on historical records and memoirs, Lee constructs a seven-day time period with video and creative writing, re-enacting the psychological changes and conflicts of the refugees during the long journey of escape and repatriation, thus exploring the complex process of identity ‘transition’ under the sudden change of politics. Through a group participatory approach to filming, Lee draws on the subjectivity and creativity of the local participants to bring to life the sense of emptiness inherent in a multi-layered historical and collective consciousness, where the confusion about identity intertwines between history and the present:

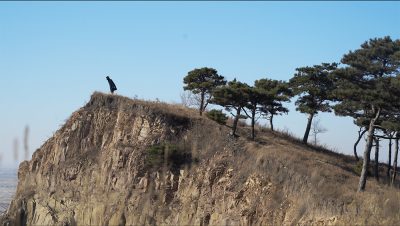

It took some time for the Jewel Voice Broadcast to reach the village – the leader had run away early in the morning and they, the olderlies and the children, were the only ones left behind. “The war was a decision made by adults and men.” said the female emigrants, they then reluctantly followed the order to leave the village of Shadow Lands in the ‘New World’ and walk to the nearest city and shelter to await repatriation. The only way to avoid the troops from the north was to bypass the main road and take the dense forest. From the heat of the northern summer to early winter, they put on all the layers of summer clothes they could carry. Along the way, a flock of crows hovered overhead, thinking that the emigrants would not live long. They met different people along the way, and because nature is always cruel, fewer and fewer companions were left. After a few months in the repatriation facility, they were finally taken to the pier, but they were drained. Suddenly the song came from afar, just as it had every morning in the past, when everyone had stopped working and listened in silence as they ploughed the fields of the Shadow Lands. But this time, when they looked back in a flash, they lost for words and focus because the song was familiar but not quite the same.

During his research, Isaji was struck by a travel guide to Manchuria that he happened to read – in addition to the pleasant text featuring local attractions and souvenirs from Manchuria, the title page also featured the Manchukuo national anthem. Songs that were once commonly used to convey emotion and reinforce tradition became top-down propaganda to unify national identity in the hands of the regime. The grand visions of a ‘New World’ and ‘New Manchuria’ in the lyrics only brought a sense of alienation and oppression to the public. The Manchukuo national anthem, which has been modified into several versions due to its political metaphors and bewildering lyrics, eventually became a silent fragment hidden in history, just like the deliberately erased memories of that period. Isaji made field recordings during visits to the repatriation sites in Japan, and maps into the rhythm of the Manchukuo anthem, aiming to respond to the absurdity of the hollow regime and unplanned emigration policy, and a re-examination of a history hidden behind a modern landscape.

In response to the travel restriction during global pandemics, the artists adopt an alternate research methodology to conduct fieldwork and interviews in their own countries, their works are intertextual and complementary in order to respond to the complex and diverse identities in histories of the Manchurian region. In the passage of time, the audience follows the steps of the settlers through the mountains and forests of the North. Suddenly, a foreign rhythm is heard from nowhere, and like the people in the images, the two artists’ visions meet.

Credits:

Director and writer: LEE Kai Chung

Researcher: SHEN Jun | ISAJI Yugo

Production

Production Manager: JIANG Junchi

Production Assistant: LI Wenxuan | Maggie CHANG

Camera

Camera Director: LEE Kai Chung

Cinematographer: JIANG Junchi

Cinematographer (B Cam): LIU He | WU Wenli

Drone Pilot: LEE Kai Chung

Postproduction

Editor, Colourist: LEE Kai Chung

Translation (Chinese-Japanese): Hiko LEE

Translation (Chinese-English): Bill LEVERETT

Sound

Sound effects: LEE Kai Chung

Sound mixing: NOZAWA Mica | ISAJI Yugo

Music: YAN Yulong

Voice-over recording technician: IKEDA Ryo

Cast

FEI Shihuan | LIU Xinyu | ZHANG Yifan | Cong Miao | AI Ziyuan | TIAN Yicen | MIAO Jiayu | LIU Guiling | Chong Er | LU Fengrong | SHEN Jun | LEE Kai Chung | LI Yu

Voice-over Talents

ISAJI Yugo | ADACHI Momoyo | TOYAMA Hisae | MORI Yuna | TSUGA Megumi | SAITO Haruka | HIRAKO Shuto | IKEDA Ryo | KAWAKAMI Hatsuko

Special thanks

He Xi | FU Jingyan | HUANG Wanshan, Cat | LI Zhiyong | PAN He | SONG Yuanyuan | XIE Tianhao (Acherozu) | ZHANG Lu | ZHU Jianlin

Acknowledgment

The project is supported by the Hong Kong Arts Development Council